The man without a plan

Peter Dutton's constant backflips reveal a politician adrift, lacking both vision and the resolve to differentiate himself from Anthony Albanese.

This post follows from last week's Deep Dive into Albanese's Labor government. While politics isn't exactly my forte, it's inseparable from economics—ultimately it's the politicians in power who determine which economic policies are pursued, not the economists.

Now, Peter Dutton is unlikely to win the election—he's trailing in all the polls and on prediction markets, and the election is less than two weeks away. But stranger things have happened, so on the off chance that he does form government, here's my take.

Who is Peter Dutton?

He might not have had a stint as Prime Minister, but Peter Dutton has been an elected official for a long time—24 years, in fact. He served as Minister for Workforce Participation and then Revenue in the Howard government; Minister for Health and then Immigration in the Abbott government; Home Affairs under the brief Turnbull government; and finally Defence in the Morrison government.

That's a fair bit of experience, and comes with a long voting record that shows, above all else, an unwavering loyalty to the party—Dutton has never cast a vote against the majority of the Coalition. And that's basically it; he's a conservative, through and through:

"He stands up for what he believes in," [longtime pollster Kos] Samaras says. "Voters may not like him, but they appreciate he is a politician who stands on his beliefs. That was a brand he developed during the Voice referendum. But that's the only definition that exists. Voters have no other impression."

There's a time and a place for such a politician. For example, after the turbulent Morrison/Frydenberg years, all Anthony Albanese had to do was pretend to be a normal, relatable human being for a few weeks.

All Scott Morrison had to do in the election prior to that was not be Bill Shorten.

But there's now a right-of-centre madman in the White House, and the left-of-centre Albanese government can hardly be accused of being too erratic (mediocre would be more apt). If voters don't perceive enough differentiation between the status quo and the alternative, and they happen to be in a state of heightened risk-aversion due to Donald Trump's trade war, then they're more likely to vote for the devil they know.

More backflips than Cirque du Soleil

If the election had been held a year ago, Dutton probably would have won. He successfully campaigned against the Voice referendum, and was a welcome breath of fresh air for a society that had grown tired of the wokeism that had seemingly infiltrated every walk of life.

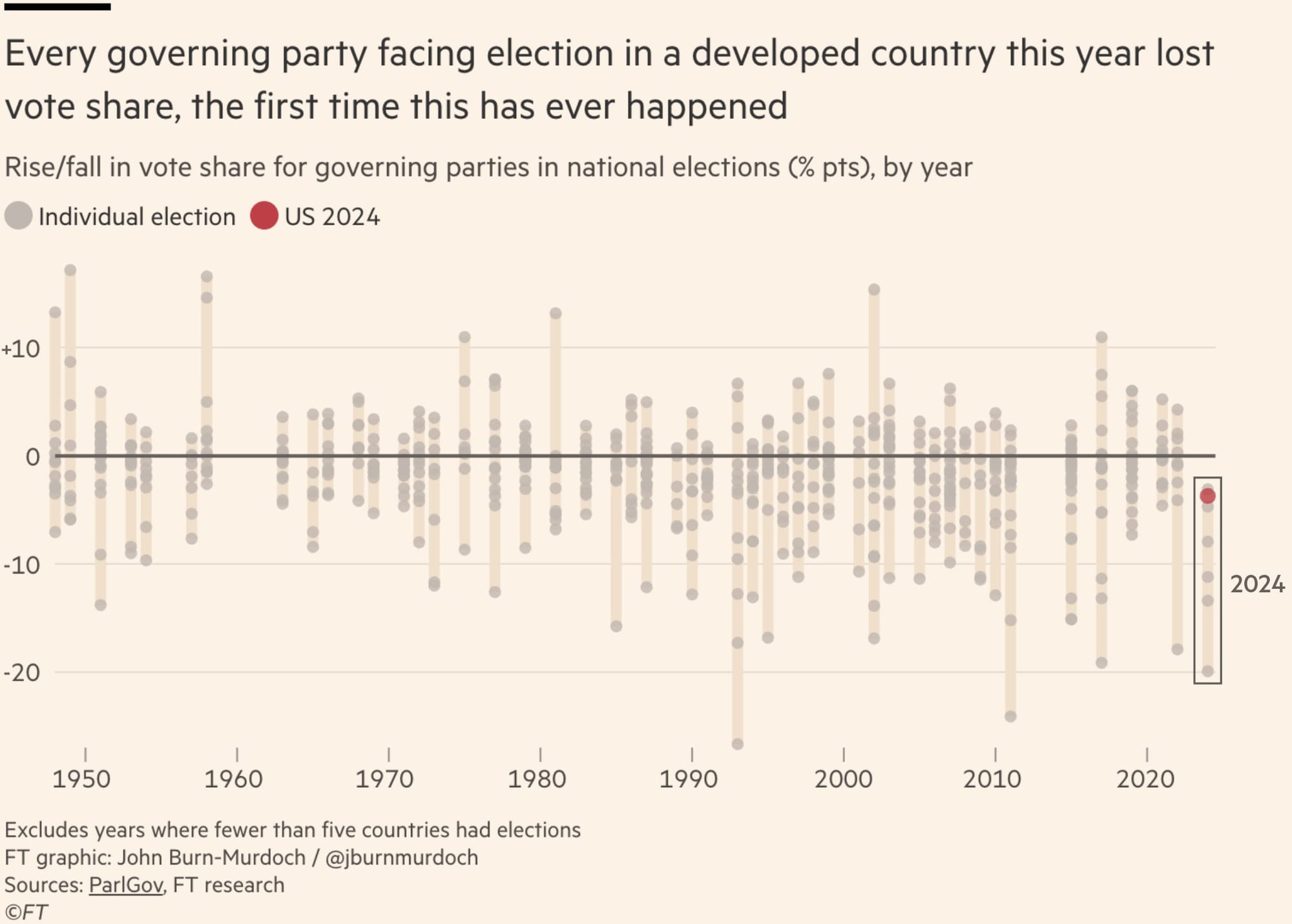

The Albanese government also managed to absolutely botch the inflationary cost of living crisis, and in 2024 global incumbent governments lost nearly every election they faced.

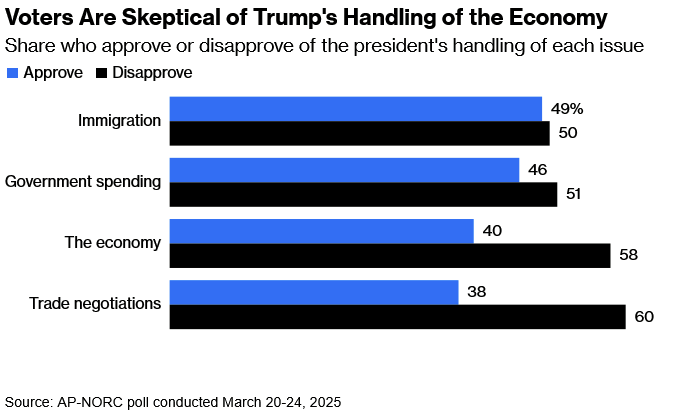

But then along came Donald Trump. While people are largely satisfied with his anti-woke and anti-immigrant agenda—or at least their views on those issues haven't changed all that much since November's election—the public's opinion of his economic management and trade war has plunged.

Very few people expected Trump to go—to quote Tropic Thunder, "full retard"—on tariffs. But he did, and suddenly incumbent governments were back in vogue.

That forced Peter Dutton, who had echoed many of Trump's policies including establishing his own Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) and taking a hard stance on cultural issues, and whose front bench had boasted they would deliver "the exact same attitude [as Trump]", into his first reversal.

While I certainly respect someone who's willing to change their mind in the face of new evidence—in fact, that's about the most anti-Trumpian trait one can possess—in politics it can give the impression that you're weak and have no convictions; that you're willing to say or do anything to get elected.

To be clear, that's exactly what any politician would do. Just like the rest of us normies, they act on the incentives they face, and a politician's primary priority is to get elected or re-elected. But through all of his pivoting, Dutton is effectively saying the quiet part out loud: voters want to believe that politicians are acting in their interests—for the greater good, or in service of the "public"—not because they're self-interested.

By announcing policies only to backtrack weeks or months later, Dutton comes across as a man without a plan; someone who only makes up his mind on something once he has run it past several focus groups. It's a strategy that is so obvious that satirical groups have been having a field day.

Too many "mistakes"

What was especially interesting to me is that, while researching this post, I concluded that every single backflip was for the better—some of Dutton's ideas were truly awful. It's almost as if he hadn't thought all that deeply about many issues, instinctively reacts to a question from a journalist or in Parliament, and then his team goes into full damage control trying to convince him to walk it back.

Most recently, Dutton's hard-line response to the supposed Russian air force base in Indonesia, for which there was little evidence, is a good case in point—"a mistake" that he shouldn't have made, had he done even a little bit of due diligence before making such a rash statement.

But there's a long list of Dutton announcements and subsequent backflips, so let's go over a few in order of their electoral impact.

Cutting the public service

In true Trump style—Dutton was using a similar playbook up until the situation over there went... pear-shaped—Dutton criticised Labor's expansion of the public service and said that if elected, he would fire 36,000 workers.

By January 2025 that plan had been formalised into a "government efficiency" platform, with Senator Jacinta Price named shadow minister, and the number of staff would be reduced by an even greater 41,000 by 2030.

But when headlines about all the dodgy stuff Elon Musk's DOGE had been getting up to combined with the rapid decline in Trump's popularity, Dutton pivoted: no public servants would be fired, there would simply be a hiring freeze and a reduction in staff would be achieved through natural attrition and a yet-to-be-determined number of voluntary redundancies.

But it was a bad policy from the get-go. In fact, in my experience it's precisely the wrong way to go about improving government efficiency. We've known about how bureaucracies tend to cycle into rigidity since Anthony Downs' Inside Bureaucracy (1967). Periodic reform and changes to governance structures are needed to 'shake them up'.

Regardless of how he plans to achieve his cuts, Dutton's hatchet job does none of that and will come with a litany of unintended consequences.

The 'type 2' bureaucrats who favour a quiet, secure career—and generally don't care for, or even actively resist, controversy or innovation—won't go anywhere. Neither will the dead weight that sit at their desks but do very little, creating more work, stress and frustration for their remaining colleagues.

That means the only people leaving will be retirees and those with marketable private sector skills (including overworked, highly productive employees). The end result will be reduced state capacity and the temptation to fall back on expensive consultants to fill the holes, as happened under the Morrison government.

What Dutton should have done instead is offer a point of differentiation, not just with Labor but with previous Coalition governments. You don't need a hatchet, but reforms that improve organisational efficiency and meritocracy of the bureaucracy. Evidence from the US suggests that empowering managers—i.e., giving them more say over firing and hiring decisions—and limiting the role of unions at the federal level can improve state capacity, saving the budget in the long run:

"These reforms have made many or almost all state employees at-will, decentralised hiring capabilities to agency managers, allowed more variation in pay based on capabilities and performance, and limited collective bargaining with public employee unions."

Such reforms would be perfectly consistent with Liberal values.

But it gets worse, because Dutton's take is also backwards: you need to address the reasons why all those public servants were hired before culling them. For example, you wouldn't slash ATO workers without first simplifying the tax code, right? As management consultant Peter Drucker wrote:

"In many if not most cases, downsizing has turned out to be something that surgeons for centuries have warned against: 'amputation before diagnosis'. The result is always a casualty."

A better approach would be to address the Byzantine processes and requirements that make everything take longer and be more expensive than necessary. The 2019 Thodey Review found that 40% of employee time was "being spent on highly automatable tasks such as data collection and processing"—address that before you even consider taking out the hatchet to the employees doing the work, the number of which is still below Howard-government levels (as a share of the population).

Dutton's public service strategy is a great example of shallow, short-term thinking designed to create a headline, but voters will see right through it.

Working from home

Dutton's return-to-office mandate was a loser from the get-go, yet he stuck with it for months before embarrassingly throwing in the towel and admitting that "we made a mistake".

Regardless of what you might personally feel about working from home, there's strong evidence that flexible working arrangements:

- reduce office and wage costs (more on that below);

- improve recruitment and lower retention costs, and staff attendance (fewer sick days);

- cut congestion and pollution through less commuting; and

- support those with care and disability challenges.

Yes, that's all also true for government workers. And in Australia specifically, there's "no significant difference in productivity between employees who work from home and those in the office".

Dutton wasn't helped by the fact that, when announcing the policy, his shadow finance minister Jane Hume "cited research that actually endorses partial work from home". And that women with young children are the most likely people to be taking advantage of remote work—and Dutton already had a women problem.

As with taking a hatchet to the public sector, it all just reeks of policy on the fly—Trump did it, so we should too... until we didn't want to be associated with him anymore, so now it's no longer Liberal policy.

But as before, if Dutton had done his homework he could have taken a completely different tact that would have kept everyone happy while also reducing the public sector bloat he so detests.

For example, there are costs to working from home, such as a reduction of internal knowledge transfer. That can be solved with better managerial techniques, especially if workers are in the office at least a couple of days a week—a great way to sell public sector productivity reforms!

Many employees also value working from home a lot—on average, they may be willing to take a 25% pay cut for partly or fully remote roles. Across the entire US economy, Stanford's Steven Davis estimated that one reason wages stagnated even with high inflation is because people were willing to accept a real wage cut to keep their remote privileges:

"[T]he big shift to WFH lowered average wage growth by two percentage points from spring 2021 to spring 2023, and it likely exerted downward pressure on wage growth outside of this time interval as well.

...

By exerting downward pressure on wages and other labour-related costs, these developments eased the way for a sharp reduction in inflation with no rise in unemployment – even before the effects of monetary policy tightening added to the disinflationary pressures."

Similarly, The Economist noted that at computer giant Dell, "half of employees opted to stay remote last year, even when bosses made it clear they would not be promoted if they did so".

Studies have found that many people are willing to accept reduced pay in exchange for the ability to work from home, which can increase overall welfare. Coming to some kind of compromise would be a win for workers and the federal government.

Now, I don't know what form that might take: perhaps something like a voluntary 5% pay cut per day working from home (or a 5% pay increase per day in the office, if you prefer a carrot approach). But what I do know is that Dutton's blanket return-to-office mandate guaranteed that no such mutually beneficial exchange would be possible, frustrating workers and managers alike—and hence the eventual backflip.

Breaking up the big supermarkets and insurers

When presented with a problem, Dutton clearly prefers a hard-line, big-government response. For example, he called Albanese "weak as water" on the supermarkets because he wouldn't commit to forced divestiture, which Dutton unveiled as a Liberal policy in July 2024:

"Today, we announce the Coalition will introduce sector-specific divestiture powers as a last resort to manage supermarket behaviour and address supermarket price-gouging.

Divestiture powers will address serious allegations of land banking, anti-competitive discounting, and unfairly passing costs onto suppliers."

He also said "we will intervene" by forcibly breaking up large insurance companies, only for his shadow treasurer and finance ministers to promptly rule it out.

What this shows is that Dutton doesn't understand the basic economics of competition, and appears to be declaring policy without first consulting his team—and neither is a good look. He also has some bee in his bonnet about big business, conflating industry concentration with a lack of competition. But as I wrote last month:

"[There's] decades of economic research that shows concentration is a poor measure of market power—indeed, strong competition can even increase concentration as the most productive companies win market share and benefit from scale economies. That's generally a good thing for consumers, provided entry and exit remains free."

There's a lot that could be done to improve the functioning of Australia's supermarket and insurance markets, such as fixing planning and zoning laws (as recommended by the ACCC), and getting rid of Albanese's insurance subsidies that incentivise people to live in risky locations.

But once again, Dutton appears to be blissfully unaware of the economic literature and the actual state of the market he's discussing. He seemingly wants to take a 'big stick' approach to everything, even when larger firms can offer products at lower prices, and so smashing them into smaller pieces would likely raise prices for consumers.

It's not just that it's frustratingly bad economics. It's also an approach that goes against fundamental Liberal values, meaning he can't use the issue as a point of differentiation with Labor.

Tax reform

In February 2024, Dutton pledged to:

"We will take to the next election strong tax reforms in keeping with the stage three tax cuts that deal with that insidious thief in the night.

You will see strong policies from us on tax reform in line with the principles of the stage three tax cuts."

But by November, that had morphed into:

"[Tax cuts] depends on where the numbers are as we go into the election and how much money is available and how we prioritise our spending and how we do it in a way which is targeting inflation, so that interest rates can come down."

And then earlier this month it had become:

"Our [$1,200] Cost of Living Tax Offset will put more money back into the pockets of millions of Australians at a time when they're being crushed by skyrocketing grocery bills, rent, mortgage repayments and insurance costs."

So, to recap: bold tax reform became no tax cuts, which then became a temporary tax cut, along with a weird pledge to block Labor's permanent $5-a-week tax cut.

It's all very confusing, and if voters wanted a choice between Labor and a fiscally disciplined alternative, they certainly haven't got one from Dutton. Even his plan to establish a "Future Generations Fund" to pay down debt involves adding to the nation's debt, while structurally weakening the Budget. The same is true for his fuel excise cuts, which undermine whatever green credentials he might have had (helping the Teals), add to the debt, and do nothing to boost productivity or improve the efficiency or equity of the tax system.

Add all of that to the puzzling decision to push for a small to medium business $20,000 deduction for lunches and entertainment—which has barely received a mention during the campaign—and it's clear that Dutton doesn't have a tax policy, let alone a plan for tax reform.

But perhaps most bizarre was, in an interview that aired just before the long weekend, Dutton "said ambitious tax reform would only come when the budget could afford it":

"He made clear indexation of the tax rate scale was not a promise he was making at this election. But it was an aspiration he intended to honour as prime minister."

I'm sorry, but no. You're either committed to tax reform, or you're not. Australians aren't stupid enough to fall for the "when we can afford it" line; we're always only a few months away from the next crisis that inevitably kicks the reform can down the road to the next election.

If Dutton truly wanted to differentiate himself from "Labor's long line of deficits", then he needed to differentiate himself. Labor also talks about its "aspirations" for running surpluses, but the public knows that political promises aren't worth the paper they're printed on—we'll believe it when we see it!

The fact that this "aspiration" of Dutton's was only revealed to voters just prior to the Easter long weekend, and less than two weeks before the election, gives the impression that he's a man who doesn't truly believe what he's saying.

Does Dutton actually want to index the income tax, or is that just what his latest focus groups are telling him to say?

Immigration targets and indigenous recognition

Two additional backflips further illustrate Dutton's inconsistency. First was his plan to ban all Gaza refugees, which later became a pause. Then there was his promise to slash Australia's migration targets from 185,000 to 140,000, which was later dropped entirely, only to resurface again as a 100,000 cut to net overseas migration.

I've written about the problem with quotas before, and while immigration policy is tricky, it surprises me that a Liberal government—normally considered to be friendly to markets—is so averse to using the price system to achieve its goals.

To be clear, cutting immigration might lower housing costs a bit, but it would also hurt Australians overall. Fewer workers—especially skilled migrants who drive innovation—means an older country with less economic activity, worsening the budget deficit and slowing growth. That might be a trade-off worth considering, but it's critically important to get the balance right, something Dutton hasn't so much as mentioned as a consideration.

Finally, there was Dutton's obsession with referendums. He has called for three separate issues to be taken to the polls: "indigenous recognition, four-year parliamentary terms, and stripping citizenship of dual nationals".

He has since abandoned all three, but one can't help but wonder where Dutton truly stands on these issues. Does he believe what he initially proposed? Will he just backflip again as soon as he's elected? No one knows, and such uncertainty can be anathema to a politician's electoral ambitions.

Remarkably unremarkable

The rest of Dutton's policy proposals are, quite simply, unremarkable. They're mostly Labor-lite: whenever Albo reveals a big spending plan, such as his huge election-eve Medicare spend, Dutton matches it within hours.

When Labor bailed out the Whyalla steelworks, instead of standing up for traditional Liberal values—Whyalla was also bailed out by Turnbull in 2016, making me question whether those values still exist in the party—Dutton promised to match state and federal funding commitments.

Then last week, after Albanese announced a truly awful housing policy that will stimulate demand and making housing less affordable, Dutton promptly matched with his own equally bad version.

To be fair, these aren't Dutton-specific problems; as economist Chris Richardson observed, it has been the pattern for decades:

"[O]ur oppositions have promised their taxing and spending to be more than 99 per cent matching those of the government they're campaigning to replace.

In the election campaign both sides are therefore promising Australians that they'll remain mediocre."

Dutton had a golden opportunity to break that trend, but he has almost certainly blown it by failing to offer true differentiation. Voters are tired of the Albanese government, but not enough to toss the bums out after a single term—especially not with spectre of Donald Trump floating around.

Indeed, even when Dutton did differentiate himself, such as with his bold move to support nuclear power to diversify Australia's energy mix, his execution—favouring seven large-scale, state-owned nuclear plants—lacked the nuance needed for Australia's renewables-heavy, liberalised electricity market.

But it didn't have to be that way. All Dutton had to do was acknowledge that the times had changed, and all he wanted to do was legalise nuclear to allow innovation in the energy space—a position much more in-line with Liberal values than a huge, costly state-owned public works project.

The fact is the viability of such large, vertically integrated energy utilities has been fading because of competition from solar and battery storage. And while they're still commercially unproven, economically competitive small and advanced nuclear reactors are one day likely fit perfectly into such a model—and are already being built in many countries, most recently by Canada. And now because nuclear is tied to Dutton, a loss would mean Australians may never benefit from innovations in that space.

I was that was the end of the missteps, but Dutton's gas reservation policy falls into a similar bucket: instead of trying to remove the roadblocks to gas exploration and production—again, a position perfectly consistent with the Liberal Party—Dutton wants to use the strong-arm of government to force gas companies to divert current production to the Australian market at below-market rates.

It's a plan that's rife with problems.

First, given that it excludes WA gas, it might violate the Constitution, "provoking an expensive High Court battle with fossil fuel giants", and companies may sue the Australian government for "lost profits" using treaty law.

Second, it's wasteful: instead of exporting gas to markets where it's more valuable, some of it will be used domestically to prop up inefficient domestic industrial projects and reduce households' bills. The capital and labour drawn into those industries, along with the revenue never collected from selling the gas internationally, reduces the standard of living for all Australians.

Do a few industrialists benefit? Sure. As do many households, which will pay lower energy bills and/or use more energy. But they lose everywhere else because of the lost efficiency—lower wages, more expensive goods, higher taxes, and so on.

Third, a reservation policy might reduce the amount of capital available for future gas projects because the returns will be lower, so over a period of say 30 years, average power prices may even be higher than with no reservation policy.

As with cutting immigration to "solve" housing, Dutton's gas policy would create unintended long-run consequences that outweigh the benefits, reducing the nation's overall welfare. But don't just take my word for it: in 2019 academics took a look at the existing WA gas reservation policy, finding that it "imposes an overall net loss to the nation of around $600 million each year".

It might still be worthwhile for energy security reasons, but there's no question that it will reduce living standards, and doing it after investors have sunk capital is a recipe for ruin.

Three more years

Assuming the leadership position after the Liberal Party had suffered its worst electoral defeat since its formation in 1948 was always going to be a tough ask, so I don't entirely blame Dutton for his underwhelming performance.

To me, the most depressing aspect of this election has been that it is essentially borrowed from the US playbook: a boring version of Harris vs. Trump, with barely a single bold policy proposal offered from either side.

There should be a much more serious policy debate happening. Instead, regardless of who wins next week, Australia looks set to tread water for three years while the economic problems that ail us compound. Structural fiscal deficits during a period of full employment? Zero productivity growth for a decade? A tax system that hasn't seen any meaningful reform for a quarter of a century?

Deathly silence from both major parties.

Instead of offering a point of differentiation with Albanese on these critically important issues, Dutton chose to match all the big spending while tinkering at the margin of the culture war with things like anti-racketeering laws.

After writing all of this, I'm still left wondering whether Dutton genuinely believes anything he says, or if he's simply along for the ride, doing whatever it takes to get himself and his Liberal Party colleagues elected. No doubt many others are equally unsure about what a Dutton Prime Ministership would actually look like—and that's a big reason why he's unlikely to win it.

In short, Dutton's inability to distinguish himself from the current government, paired with his inconsistent policy positions, offers voters a choice that feels more like an echo of Labor than a fresh alternative. It's probably too late to right the ship before this election, but if the Liberal Party wants a shot in three years then it needs to rediscover its values, address the big issues, and find a sharper, more consistent voice to reconnect with a public that's tired of political sameness.

Have a great day.